- Home

- Fang Lizhi

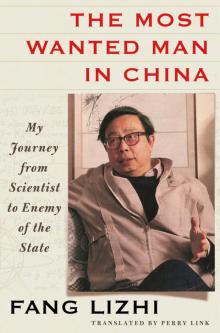

The Most Wanted Man in China

The Most Wanted Man in China Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

About the Author

Copyright Page

Thank you for buying this

Henry Holt and Company ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on the author, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

FOREWORD

by PERRY LINK

When Fang Lizhi, one of China’s most distinguished scientists, began in 1986 to talk to his students about the “universal rights” of human beings, he knew the risks. In those days, the use of the term “rights” in China was highly sensitive, even dangerous, and three years later Fang would pay the price for his candor. He spent the last twenty-two years of his life in exile from China, but his ideas, on their home turf, were not so easy to stamp out: the concept of “rights” lived on, and it gradually became less perilous to mention the word. In 2003, a “defend rights” movement took root among Chinese lawyers and activists, and by the time of Fang’s death in 2012, factory workers, miners, petitioners, and even farmers in small villages had begun to conceive and pursue their interests as “rights.” The trend had grown beyond anything China’s rulers could reverse. It was a sea change and thus had many causes; no person did it single-handedly, or could have. But if we ask which person, among the many, did the most, the name Fang Lizhi must surely arise.

A brilliant physicist, Fang was recruited out of college to work on Mao Zedong’s project to build an atomic bomb. Later he became one of the youngest people ever appointed to China’s Academy of Sciences. When he began speaking out about human rights, he was already vice president of the prestigious University of Science and Technology of China. It was the highest position from which anyone in China had ever stepped out to be a “dissident.” Fang’s admirers have likened him to Andrei Sakharov (1921–1989), the Soviet physicist who, like Fang, worked on nuclear weapons for a Communist state, later turned to human rights advocacy and dissent, and eventually was punished by exile (internal in Sakharov’s case, external in Fang’s). Sakharov won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1975. The conditions of the Cold War, added to the fact that Russia has closer ethnic and cultural ties to the West than China has, can explain why Sakharov is better known in the West than Fang is. But they are kindred spirits, and Fang’s historical legacy is at least as large.

For Fang as for Sakharov, rights were implied by science. This book shows how, step by step, it was the axioms of science—skepticism, freedom of inquiry, respect for evidence, the equality of inquiring minds, and the universality of truth—that led Fang toward human rights and to reject dogma of every kind, including, eventually, the dogma of the Chinese Communism that he had idealistically embraced during his youth.

Fang entered world headlines on February 27, 1989, the day after the Chinese police had barred him and his wife, Li Shuxian, from attending a barbecue banquet in Beijing to which U.S. president George H. W. Bush had invited them. They were in the news again after the Tiananmen Square massacre of democracy advocates on June 4, 1989. Late at night on June 5, staff from the U.S. embassy in Beijing, acting on instructions from the White House, invited the Fangs, who were then at the top of a Chinese government “wanted” list, to take refuge in the U.S. embassy. They accepted and stayed for thirteen months, sealed in a secret location, while “the Fang problem” became a major headache in American foreign policy. (On June 26, 1989, Fang received a note of support from Andrei Sakharov; this was six months before Sakharov died.) In the final chapter of this book, Fang reveals the negotiations that led to his and Li Shuxian’s release from the U.S. embassy. They went to England, and then to the United States, where Fang settled at the University of Arizona and resumed his career as a professor of astrophysics. He was teaching full time when he died.

Many histories, biographies, and works of fiction have been written about the saga of the Communist movement in modern China—how it rose, inspired hope, and then brought disaster; how the Party survived, adapted, got rich, and lumbered on. No book, though, does better than this one at giving a sense for what the whole epic experience felt like from the inside. I say this for several reasons.

For one, Fang is a gifted writer. In high school he won essay contests, and the talent shows. His insights are deep, he illustrates them in vivid detail, and he is utterly honest. Other Chinese writers can rival him in some of these regards, but none can match his reach: from his early life in Beijing alleyways to his encounters with top political leaders, it is the same astute, observant Fang Lizhi who is our guide. He explains how water was delivered in premodern Beijing, how farmers catch pigs, and why students at China’s leading technical university in the mid-1980s ate their meals standing up. From personal experience of “labor reform,” he tells us how wells are dug by hand and how a railroad construction crew rolls boulders down a mountainside without killing anybody. He doesn’t flinch when the topics turn hideous: how victims of political persecution select their means of suicide, and how people guard the gates at morgues to prevent wild dogs from eating the corpses of their friends or relatives. The same matter-of-fact voice shows us a vociferous public debate he has with Wan Li, one of China’s highest officials.

He is as honest about himself as on any other topic. Other Chinese intellectuals, when they look back at the 1950s and 1960s, tend to see themselves—and rightly so—as victims of Mao Zedong and his regime. They often do less well at explaining their original attraction to Communism. But not Fang. He explains how, as a high school student in the late 1940s, he despised the corruption and incompetence of the Nationalist government, was captivated by the prospect of Communism, and joined an underground organization at a time when doing so could cost one’s life. On a rainy night in 1949 he stayed up past midnight at an outdoor stadium, literally dancing in anticipation of his first chance to see Mao Zedong in person. In college, from 1952 to 1956, he fell deeply in love with physics, with Communism, and with his girlfriend Li Shuxian, who was his classmate and herself a physicist and sincere Communist. He saw his shining future resting on a tripod—physics, Communism, girlfriend—each leg sturdy, each supporting the ideals of the other two.

Soon, though, the physics and Communism legs came into conflict. Science asked him to begin in skepticism and to build knowledge by hypothesis, evidence, and proof—from the bottom up. In Marxism class, on the other hand, he was given the right answers on the first day and told to work from the top down. And there were other anomalies: for science, truths are universal; Mao Zedong said that truth has a “class nature.” Science thrives on the free flow of information, but the Communist organization directed information only to certain people and only under certain conditions. These anomalies, at first only irritating, grew deeper as Fang’s college career moved on. Then, in the late 1950s, intellectual quandary turned into real-world pain as Fang was torn away from physics and from his girlfriend and sent to do labor in a small farming village in Hebei Province. What most shocked him in the village was not his own suffering but the degradation of the “peasants” who—it had been said in Marxism class—were the “vanguard of the revolution.” Communist theory was suddenly revealed as a pompous abstraction.

Fang’s disillusionment grew deeper

a few years later during another stint of labor reform, this one at a coal mine in Anhui Province. There, at the bottom of a mine, his political faith hit bottom as well. He found that the miners—the quintessential “laboring masses” in Communist imagery—were the victims, not the agents, of the “proletarian dictatorship.” In this regard they were like the intellectuals: the authorities exploited both groups, only in different ways.

With Deng Xiaoping’s “reform and opening” in the early 1980s, Fang gave the Party one more chance. He had been expelled in 1958, but he rejoined the Party and went around making speeches urging young scientists to do so as well. His reason? Not that the Party was doing well, but almost the opposite: the Party holds the reins of power, he argued, and this fact will not soon change; it does govern badly, but this fact will change only if people with better ideas join and work from within.

In 1983, on a trip to Germany, Fang crossed from West Berlin to East and, immediately upon arrival, had the odd feeling that he had been to this place before, even though he plainly had not. The streets were gray, the monuments were pretentious, the border was policed. The whole atmosphere was all too familiar. The guides wanted to sell him East German postage stamps and wanted to be paid in Western hard currency. Marxist culture, he saw, can trump and homogenize national cultures.

Thirty years out of college, Fang was more strongly attached to science than ever, but his attachment to Communism had completely disappeared. The process happened step by step, despite his having granted the benefit of the doubt at every turn. First, Mao was a hero. Then, no, Mao did some absurd things—but can’t the Party correct them? No, the Party turned out to be an elite of self-interested power engineers—but doesn’t Marxism itself deserve better? No, Marxism is not the answer; it apparently spreads the same shades of gray everywhere. After 1987, when Fang was expelled from the Communist Party for a second time, he found himself a “dissident.” There seemed no other way.

In describing the bloody Tiananmen Square repression of June 1989, Fang sets the events against the wartime memories of his boyhood:

Here’s what happened: the central government of China mobilized 200,000 regular troops, supplied them with regular military weaponry (tanks and submachine guns) and used regular military formations and tactics to force an entry into its own capital city, territory that it already held.

After students and other civilians were massacred, Party leaders blamed Fang for starting the whole thing by inspiring the students, and, as noted above, he and Li Shuxian took refuge inside the residence of the U.S. ambassador to China.

Confinement there was tight, but of course it was better than prison, and it provided enough spare time for Fang to draft this book. “It seems a good time,” he writes in his introduction, “whether in order to understand the past or to interpret what will come next, to do a review of where I have been so far.” He began writing in October 1989 and finished the book shortly after leaving the embassy in June 1990. Li Shuxian has told me that his routine in writing was to conceive one chapter at a time, organize its structure in his mind, and then just sit down and write it out rather quickly. One can only marvel at his memory. Working with no library, no Google search function, and very few notes, he named dates, times, and places, and quoted from letters and documents, in ways that have held up extremely well under my fact checking.

Fang’s allies in the struggle for democracy and human rights in China have sometimes misunderstood the depth of his devotion to science. It was always his north star, however the rest of the heavens might spin. When he entered the U.S. embassy, some activists criticized him for not choosing political martyrdom instead; when he exited the embassy, some were disappointed that he turned down leading positions in the overseas Chinese democracy movement in order to be a professor of astrophysics. But these criticisms reflect a misunderstanding of the man. Throughout his life, Fang saw himself as a physicist who had duties as a citizen. At several points in the 1980s he chose physics over opportunities to move upward in Chinese officialdom. Later, during his exile years, he counseled young Chinese democracy advocates against careers as “professional activists.” He advised them to be physicists, computer technicians, teachers of Chinese, or whatever—and to be citizen activists on the side.

Fang himself had the capacity to do many things “on the side.” His powerful brain enabled him to focus on a wide variety of topics beyond his academic pursuits. He sometimes seemed charmed by his own good luck in having such a super-brain and played with it almost as if it were a toy, pointing it here or there to see what would happen and then noting down the interesting results. In this book he takes us on many and diverse short detours through topics in both Chinese and Western learning. The history of science gets a great deal of comment. He finds, for example, an uncanny convergence between passages in Galileo and in China’s ancient Book of Documents on a conceptual point that undergirds modern relativity theory; he explains how Johannes Kepler used pitch intervals and rhythms to describe the speeds and oscillations of planetary movements and then relates the theory to problems of perspective in viewing contemporary China; and he compares accounts of the different colors of stars in Sima Qian’s Records of the Grand Historian (ca. 100 B.C.) to spectral measurements of star color in modern physics. But he also addresses history more broadly. He recounts a visit to Malam Jabba in Pakistan, where the seventh-century Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang, who traveled to India in search of the true Buddhist scriptures, crossed the Karakoram range on his way back to China. Fang’s account of Xuanzang, reaching back thirteen centuries, makes an ancient world seem as vivid as today’s. On a trip to Japan, Fang learns how Chinese merchants who ventured to Japan in the days when ocean travel depended on the prevailing winds were obliged to spend half of each year, including festive New Year’s, in Nagasaki; as he paints their life there, one almost feels that one is walking among those merchants.

About once or twice per chapter, Fang’s language turns lyrical, challenging its translator to capture its glow. Here, for example, is how he describes his elation upon arriving at Peking University as a first-year student in 1952:

It stood at a civilized distance from the racket of the city, from the traffic noise and the hawkers’ calls, and seemed elevated to its own plane of purity. When I walked through the campus in the cool air at night, past the semi-somnolent Nameless Lake and the Temple of the Flower Goddess that graced its bank, past the majestic water tower that reached toward heaven, and when I heard the bells that tolled occasionally from the clock pavilion, I had the feeling that all these signs were augurs of my future, which, like the scenes themselves, would be peaceful, harmonious, and boundless.

Fang sometimes turns a bit mystical, almost religious. He wonders at one point, with Immanuel Kant, if “the starry heavens above me” and “the moral law within me” are related. Elsewhere, after he and Li Shuxian hike to a peak in the gorgeous Huangshan Mountains, he writes:

The top is like a small island that juts out toward space, holding its own, bucking and tossing among the clouds that billow one moment and disperse the next as they blow by. The air is thin, the wind chilly; this is the frontier of the secular world, the edge where the cacophony of human loves and hates melts away. It reminded me of the “Paradiso” section of The Divine Comedy, where the highest level in Heaven is occupied not even by God but only by Dante, his lover Beatrice, and their limitless joy.

Fang’s language is always graceful, and it occasionally soars, but its most regular delights are its flashes of wit. He shows by example that even a Maoist steamroller cannot annihilate a good sense of humor. Indeed, satire is his primary weapon in combating—one might say dismantling—his primary adversary, whose image grows sharper as his account proceeds. He calls this adversary dangju, which I translate alternately as “the regime” or “the authorities.”

Dangju is not necessarily particular people, or the same people from one time to the next; it is the faceless authority that emanates from the top and ossif

ies the thinking of everyone within its system. Here is one of Fang’s many stories about dangju mentality: An astronomer at the Beijing Observatory is killed in an auto accident. The police want to record it as an “accidental death,” not a “traffic death,” because their annual quota for traffic deaths has already been filled and their year-end bonuses will be imperiled if reality does not match state planning. Unfortunately, the astronomer’s family balks at the fiction and insists that a traffic death be labeled a traffic death. Irritated, the police respond at the beginning of the next year by hanging a banner outside the Beijing Observatory: STRUGGLE HARD TO FILL THIS YEAR’S PLAN FOR THE NUMBER OF TRAFFIC DEATHS!

Fang’s tools in lampooning dangju are science and logic. Equipped with these, he fears nothing. He reads Hegel, for example, and informs us, as if awe for Hegel had never occurred to him, that the philosopher’s pronouncements on physics (he withholds judgment on other areas) are “pure poppycock and utterly devoid of value for serious physicists.” His confidence holds up just as sturdily on the street as it does in ivory towers. On February 26, 1989, that night when he and Li Shuxian were stopped on their way to George H. W. Bush’s barbecue, they got out and prepared to walk the remaining distance. Fang writes:

After only a few steps, however, a bevy of plainclothes police surrounded us to block the way. Their leader was a swarthy man with a rough manner—the very image of the kind of “hit man” the police train. He stepped forward, hooked his arm roughly under mine, and said, “I am the special agent in charge of all of security for the Bush visit. The invitation list that the U.S. secret service gave to us does not include your two names, so you cannot go to the banquet.”

This told us several things. For one, it showed that the highest priority of the highest-ranking agent in charge of security for the U.S. president was not the security of the U.S. president.

The Most Wanted Man in China

The Most Wanted Man in China